Overview

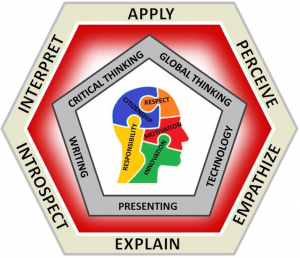

An AIS education has four areas of focus:

- Knowledge

- Understanding

- Academic Skills

- Values & Behaviors

Knowledge:

The philosopher Plato famously defined knowledge as “justified true belief”. At AIS, knowledge refers to the facts and details in the school curriculum that the students must memorize in order to help them construct deeper understandings.

Understanding:

Understanding is the ability to conceptualize and use knowledge purposefully. A student can demonstrate understanding by 1) Explaining, 2) Interpreting, 3) Applying, 4) Perceiving (one or more perspectives), 5) Displaying empathy, and 6) Revealing self-knowledge. At AIS, teachers aim to develop these six facets of understanding in their classrooms. And, by focusing our teaching on understandings, the students connect their work more closely to themselves and their surroundings, which is more stimulating, more motivating and more effective for developing lifelong learners.

Academic Skills:

Academic skills (also known as 21st century skills) equip students for constant learning throughout their lives. At AIS we group our 25 academic skills into the following five categories: 1) Writing skills, 2) Presenting skills, 3) Critical thinking skills, 4) Technology skills and 5) Global citizenship skills. The attainment of these skills is vital for adapting to globalization and the constant advancements in modern technology.

Values & Behaviors:

Values and behaviors are assessed throughout each topic as part of the school’s formative feedback system. The aim is to inform students on aspects of their behavior where they can focus attention to improve their academic performance. We group our 25 values and behaviors into the following five categories: 1) Motivation, 2) Citizenship, 3) Innovation, 4) Responsibility and 5) Respect.

AIS’ Academic Schema

International Education

The old education paradigm

In the past, education systems typically dictated what every student should learn, without regard for each child’s interests or talents. Traditional curricula were often based on the belief that each child must learn the same list of skills and then be subjected to narrow standardized tests. Therefore, students spent a great deal of their lesson time engaged in inauthentic activities involving worksheets, textbooks and standardized tests. The teachers basically assigned work, graded it and then gave it back. As a result, students became passive participants with little say in their own learning. Unfortunately, some school systems still operate in the same ways.

The international education paradigm

Fortunately, many schools are changing their ways based on modern brain research and 21st century realities. They now understand the importance of fostering creativity, entrepreneurial thinking and innovation in authentic learning contexts. Further, they see the value in giving students a say in their own learning as they develop global perspective and relevant 21st century skills. The following list highlights key indicators of a world-class education.

Empowerment

A world-class school empowers students to take ownership of their own learning: it gives them a say in school governance, and in constructing the physical, social, and cognitive school environment.

Flexibility

A world-class school promotes genuine student engagement with a curriculum that is broad and flexible. The curriculum gives students the freedom to pursue their own interests and develop their own personal talents, rather than creating standardized workers capable of all performing the same tasks.

Personalization

A world-class school personalizes each student’s education through a solid system of support. The key role of the teacher is not to direct learning but rather to facilitate it by providing sufficient emotional, social, cognitive and technical support so that students can personalize their own learning.

Authenticity

A world-class school engages students in authentic (or real-world) learning experiences that ask them to create authentic products of learning. Consequently, the students’ activities seem personally interesting, relevant and meaningful, which motivates the students to perform at a high level.

Process

A world-class school engages students in a sustained and disciplined process of learning. The students are asked to develop, review, evaluate and revise. In this kind of learning, students seek more than finding the right answers and giving them to the teacher: they are developers of useful products.

Local setting

A world-class school makes the most of its location. It capitalizes on the strengths of its students, teachers and community resources. The school’s teaching reflects the strengths of its teaching staff, and the school’s systems bring out the talents of the teachers and students.

World orientation

A world-class school operates from a global perspective, not the narrow perspective of country. World-class schools seek international partnerships, and students are engaged in important global issues. In addition, students are engaged in frequent interactions with students and teachers from other countries. In other words, a world-class education system moves students and their learning beyond the walls of their classrooms and even the borders of their country.

Global competence

A world-class school develops the ability of students to interact with others from different cultures. Thus good schools offer foreign languages and cultural learning through interactions with foreign cultures through the use of technology, field trips or the existing diversity of cultures within the school.

Teaching Standards

Standard 1: Planning, reflecting and being organized

Teachers are expected to maintain a class environment that is colorful, attractive, ergonomic and free of clutter. Class rules should be posted, and students should know the routines. Before each lesson, teachers submit a lesson plan that includes the learning aims, teaching strategies, premade assessments and materials that will be used. Lessons should begin on time with energizing warm-ups, engaging hooks to capture the pupils’ attention, and a brief review to draw out past learning. The teacher should list the learning aims and explain how they are relevant to the students’ lives. The lesson should have little down time, time-efficient learning activities, well-sequenced stages and smooth transitions. At the end of the lesson, main ideas should be summarized, and the students should reflect on what they learned and how they learned best. Additionally, the teacher should collect data from assessments and student feedback to gauge the effectiveness of the lesson and to guide improvements for future lessons and adjustments to the curriculum.

Standard 2: Creating relevant, real-world, activity-based lessons

Teachers are expected to use modern technology in ways that captivate students and enhance their learning. They should contextualize lessons by connecting the content and activities to the real world, as well as to the students’ likes, interests, talents and cultures. The students’ multiple intelligences should be targeted (i.e., logical/verbal/visual musical/bodily/naturalistic inter/intra-personal) and the students should be offered several entry points that provide multiple pathways to learning. All the activities should be aligned with the curriculum and learning aims. Additionally, teachers should encourage the students to be independent by asking them to pursue answers to their own questions through investigation, exploration, inquiry, research and creativity. And, it’s vital that the learners gain skills and understanding through meaningful activities, projects, reports, exhibits, presentations and so on.

Standard 3: Motivating students to become self-directed life-long self-learners

Teachers should inspire children to want to learn by being friendly, positive, respectful, enthusiastic, passionate, and interactive. Good teachers enlighten students by sharing unique insights and anecdotes, demonstrating passion for their subjects and displaying in depth knowledge for their subject. Teachers should motivate students by permitting them to question, explore, interact, experiment, create, innovate, be lively, and make their own decisions, all of which will give them a sense of ownership for their learning. Learners can be further empowered by having set their own goals, track their own progress, and identify their own personal strengths and weaknesses. Teachers should always demand excellence by challenging students to inquire, think deeper, take risks, be creative, make connections, and do better, whilst noting student effort, progress and success, without criticisms, to bolster their confidence.

Standard 4: Teaching for deep understanding

Teachers are expected to differentiate their learning activities (in terms of content, process and product) to match the interests, talents and readiness of individual students. Teachers should select student groups creatively and strategically (in terms of size, student interests, student abilities, and personality dynamics) to maximize collaboration and productivity. As students work on tasks, the teacher should constantly check, assist, prompt, probe and gauge the students’ interest levels, effort and understanding. Students should be asked open-ended questions (with abundant think-time) to trigger creativity, develop deep understandings and promote critical thinking. The teacher should also assess whether or not the students can make connections between parts of the lesson as well as new and old content. Tasks should be individualized so that all students are challenged, including high flyers and those with learning difficulties. All students deserve to be taught in ways that build upon what they already know and understand.

Standard 5: Assessing student understanding

Assessing for understanding means that formative assessments are integrated into every lesson to reveal which students are reaching the desired learning objectives (and which are not). And, based on the assessment data, the teacher adjusts his or her teaching activities to meet each child’s needs. Teachers should frequently assess the following six facets of understanding:

Interpret – the ability to offer plausible, supported accounts of text or data

Apply – to demonstrate/transfer understandings in new situations

Perceive– to see events, conflicts and issues from different viewpoints

Empathize– to respect differences and act upon concerns for the feelings of others

Self-understand – to know their own strengths, weaknesses, motivations and impact on others

Explain – the ability to show how you connect the dots to understand systems/concepts/ideas and make judgments/proposals

Standard 6: Teaching for the attainment of 21st century skills

Critical thinking: i. judging, ii. proposing, iii. problem solving, iv. reasoning and v. systems thinking

Global citizenship: i. contributing, ii. cultural understanding, iii. environmental thinking, iv. geography, v. valuing humanity

Technology: i. communicating, ii. web searching, iii. selecting media, iv. using media, v. visuals

Writing: i. clarity, ii. content, iii. explaining, iv. synthesis, v. technique

Presenting: i. expression, ii. fluency, iii. gesturing, iv. orating, v. reparation

Citizenship: i. leadership, ii. collaboration, iii. participation, iv. teamwork, v. positivity

Innovation: i. confidence, ii. curiosity, iii. ingenuity, iv. creativity, v. resilience

Motivation: i. focus, ii. independence, iii. interest, iv. reflection, v. enthusiasm

Respect: i. courtesy, ii. concern, iii. poise, iv. acceptance, v. gratitude

Responsibility: i. maturity, ii. accountability, iii. diligence, iv. organization, v. dependability

Curriculum

Introduction: Our curriculum aligns with National Standards and American Core Standards. Additionally, it incorporates international standards from McRel and the International Baccalaureate Programme. We presently use i-Ready and BRIGANCE assessment tools to determine each student’s learning, relative to the desired performance standards and indicators. Our curriculum is tailor-suited to meet the needs of our unique and diverse student population. Producing a custom made curriculum is hard work; it requires our teachers to review, update, and improve school documents on a regular basis. Through this process, our curriculum is becoming increasingly diversified and modernized with a variety of current topics, international perspectives and modern teaching strategies.

AIS curriculum design: The AIS curriculum is focused on the attainment of the six facets of understanding. Additionally, it follows a spiral design, which means that students re-visit topics as they advance through the grade levels – every time at a higher level of complexity and in greater depth. A spiral curriculum allows students to develop understanding gradually (at age-appropriate stages) as opposed to demanding immediate mastery. By returning to the same topics every year, the curriculum can ‘catch’ each child when he or she is ready. So if a child doesn’t grasp an idea or master a skill in grade four then he or she will get another chance in grade five. Thus readiness to learn is at the core of a spiral curriculum.

Curriculum implementation: With a spiral curriculum the teacher is not only a purveyor of content, he or she must be highly skilled in assessing readiness and differentiating instruction to match each child’s level. Furthermore, the curriculum must be well constructed to ensure that each student is challenged and stimulated (with new content of higher complexity) when a topic is repeated. This may require pre-topic assessments.

Features provided by the AIS curriculum:

Depth: AIS children develop their full capacity for thinking and learning. As they progress, they develop and apply increasing intellectual rigor, drawing different strands of learning together, and exploring and achieving more advanced levels of understanding.

Breadth: AIS children have opportunities for a broad, suitably weighted range of experiences. The curriculum is organized so that the children learn and develop through a variety of contexts within both the classroom and other aspects of school life.

Relevance: AIS children understand the purposes of their activities. They see the value of what they are learning and its relevance to their lives, present and future.

Choice: AIS children are given increasing opportunities for exercising responsible personal choice as they move through the grade levels. Choices are open but with safeguards to ensure that choices are soundly based and lead to successful outcomes.

Coherence: AIS children engage in topics and activities that combine to form a coherent experience. There are clear links between the different aspects of learning, including opportunities for extended activities that draw different strands of learning together.

Progression: AIS children experience continuous 12-year progression in their learning within a single curriculum framework. Each stage is built upon earlier knowledge and achievements. Children progress at a rate that meets their needs and aptitudes, and the teachers keep options open so that routes are not closed off too early.

Challenge: AIS children are encouraged to set high aspirations and ambitions. At all stages, learners of all aptitudes and abilities are engaged with an appropriate level of challenge, to enable each individual to achieve his or her potential.

Enjoyment: AIS children are active in their learning and have opportunities to develop and demonstrate their creativity. They are supported to develop interest, motivation and effort.

Personalization: AIS children are taught according to their individual needs, interests, learning styles and multiple intelligences. Teaching strategies and activities are developed to support particular aptitudes and talents.

Benchmarks: AIS children are assessed and compared against international standards to ensure that their learning meets or exceeds the normal achievement levels of international schools.

Understanding by Design

Teaching for understanding

Good teachers are always mindful of the difference (the “gap”) between what students understand and what they need to understand. And, they constantly seek the next steps that are needed to further each student’s understanding.

Tips to check for understanding

- Always focus on student understanding

- Always listen to what the students are talking about

- Know each student’s location on the learning continuum

- Constantly seek student feedback – through dialogue or in written form

- Constantly walk around the classroom to observe student performance

What is UBD?

- UBD curriculum planning is done ”backwards”: Goals → Assessments→ Learning Activities (all three must align).

UBD transforms Content Standards into focused learning targets based on “big ideas” and transfer tasks. UBD has the following end goals: i) student understanding; ii) student ability to transfer learning’s into the real world; iii) student ability to connect, make meaning of, and effectively use discrete knowledge and skills. - UBD teachers seek evidence of one or more of the six facets of understanding through performance tasks: when learners transfer knowledge and skills effectively, in varied realistic situations, with minimal scaffolding and prompting.

- UBD teachers are coaches of understanding, and not mere purveyors of content or activity (they plan ahead for “meaning making” by the learner).

- UBD requires an attitude of, “improvements in design and achievement are always possible”. Continuous improvement is achieved through self-assessment and peer reviews of curriculum, instruction, learner engagement and assessment results.

UBD: Stage 1

- The focus in STAGE 1 is “Big Ideas”, making sure that our learning goals are framed in terms of the important concepts, issues, themes, strategies etc. that are at the heart of learning for understanding.

- Research on learning has shown that students need to see the “Big Picture” to be able to make sense of their lessons and, especially, transfer their learning to new lessons, new issues and problems, and real-world situations.

- It is important to make explicit the transfer goal at the heart of the unit. “Transfer” refers to the ultimate desired accomplishment: what, in the end, should students be able to do with all this ‘content’, on their own.

UBD: Stage 2

- In STAGE 2 we make sure that ‘how/what’ we assess follows logically from STAGE 1 goals.

- Assessing for understanding requires evidence of the student’s ability to insightfully explain or interpret their learning: to “show their work” and to “justify” or “support” their performance/product with commentary.

- Assessing for understanding requires evidence of the student’s ability to apply their learning in new, varied, and realistic situations: “doing” the subject through performance tasks as opposed to merely answering pat questions. GRASPS is an acronym to help construct authentic scenarios for performance tasks:

Goal: the goal or challenge statement in the scenario

Role: the role the student plays in the scenario

Audience: the audience/client that the student must be concerned with in doing the task

Situation: the particular setting/context and its constraints and opportunities

Performance: the specific product or output expected

Standards: the standards/criteria by which the work will be judged

UBD: Stage 3

- The focus in STAGE 3 is “Aligned Learning Activities” that make sure that what (and how) we teach follows logically from STAGE 1 goals.

- Teaching for understanding requires that students be given numerous opportunities to draw inferences and make generalizations themselves (via a well-planned design and teacher support). Understandings cannot be handed over; they have to be “constructed” and realized by the learner. WHERETO is an acronym for self-assessing your UBD learning plan:

Where: ensure that students see the big picture (can answer the why’s; and know the expected output early)

Hook: get students interested immediately in the “Big Idea” and thought-provoking issues of the unit

Equip: provide the student with tools/resources/skills/knowledge to understand “Big Ideas” as real/important

Rethink: take the unit deeper (shift perspective, consider different theories, challenge assumptions, introduce new evidence/ideas, revise/polish prior work)

Evaluate: ensure that students get diagnostic/formative feedback, and opportunities to self-assess/self-adjust

Tailor: Personalize the learning through differentiated assignments/assessments without sacrificing rigor/validity

Organize: Sequence the work to suit the understanding goals (question the flow provided by the textbook)

What are the six facets of understanding?

- Explain: the student generalizes, makes connections, has a sound theory

- Interpret: the student offers a plausible and supported account of text, data, experience

- Apply: the student can transfer, adapt, adjust, address novel problems

- Perspective: the student can see from different points of view

- Empathy: the student can walk in the shoes of people/characters

- Self-understanding: the student can self-assess, see the limits of their understanding

What is an enduring understanding?

- The overall theme or understanding you want students to hold onto for a lifetime

- What you see when you connect all the dots (it makes sense of many separate facts)

- Shows how the content and skills tie together

- Should persist beyond one lesson (personally I have one BIG IDEA per topic)

- Should give the topic a sense of purpose (a reason for knowing all the facts and learning skills)

Enquiry Based Learning

Enquiry-based learning starts with children’s questions and with their prior knowledge and experience. Sometimes this means that teachers find themselves faced with more basic topics than those in the curriculum. However, without understanding the more basic questions, children can’t develop an understanding of the more complex ones. In order to learn to understand concepts deeply, students must have a conceptual framework to fit the information to. Learning can be thought of as constructing increasingly complex networks of connections and understandings. If we teach concepts and facts that are isolated from the students’ other knowledge, they will have little basis for understanding and remembering it. However, through enquiry-based learning, students gain skills that will serve them throughout their lives even when the curriculum content has become outdated.

How we foster student enquiry

|

|

The disposition “to be broad and adventurous” This refers to the tendency to be open-minded, to generate multiple options, to explore alternative views and to have an alertness to narrow thinking. Its purpose is “to push beyond the obvious and reach towards a richer conception of a topic or a broader set of options or ideas. Our teachers can foster this kind of learning disposition by:

Pushing beyond the obvious and seeking unusual ideas:

- How else can we think about this?

- Is there anything else we can do?

Seeing other points of view:

- How would a Chinese or American official think about this?

- What if you were on the other team, what would you think?

Look for opposites, exceptions and things that are contrary

- What is the exact opposite of the way we are thinking about it?

- What if we thought about it in an opposite way?

Challenge assumptions:

- Is there anything that we are taking for granted?

- Are we sure that we have to do it this way?

Explore new territory, go beyond the boundaries:

- Are we using the most open-ended wording of the question?

- What are some other ways to think about this that we haven’t tried yet?

The disposition “toward wondering, problem-finding & investigating” This refers to the tendency to wonder, probe, find problems, have a zest for enquiry, have alertness to anomalies and puzzles, formulate questions and investigate carefully. Its purpose is “to find and define puzzles, mysteries and uncertainties; to stimulate inquiry.

Be curious! Wonder about things!

- What do you wonder about this?

- Why might the snake rattle its tail?

Find problems, questions, and puzzles

- Why do you think the writer, artist, etc. did that?

- What would happen if the jury members were female?

Seek out what’s hidden or missing

- Do you notice anything that seems to be missing?

- What would you change if you could?

Play with “what if” questions

- What if you were invisible for a day?

- What if you could see in the dark?

Active Learning

Active learning (or student-centered learning) is a teaching approach that allows students to learn from doing activities like reading, writing, drawing, acting, talking, listening, constructing, composing, experimenting and reflecting. Active learning stands in contrast to “traditional” teaching in which the teacher does most of the talking and the students are passive.

Is active learning better than passive learning?

Research shows that students learn less from sitting passively in a classroom and absorbing the knowledge transmitted by the teacher, than from engaging in activities that cause them to question, apply and discover. In comparison to traditional approaches, active learning strategies place more emphasis on the development of skills and big ideas than on the transmission of curriculum content. Additionally, they give students more feedback to guide learning, they allow for greater exploration of student attitudes and values and they activate higher order thinking (analysis, synthesis, evaluation, etc.). Consequently, they produce students with better critical thinking skills, better retention of knowledge, higher ability to transfer new information, increased motivation and improved interpersonal skills. Thus the role of a great teacher is to minimize passive learning and maximize active learning by providing engaging activities.

What does active learning look like?

There are dozens of active learning methods for groups, pairs and individuals that fall into one of four basic categories:

Talking and listening: When students talk about a topic, whether to answer a teacher’s question or to share perspectives, they organize and reinforce what they’ve learned. When they listen to peers, they relate what they hear to what they already know.

Reading & writing: Students learn a great deal through reading, especially when the teacher provides active learning exercises that help the students to process what they’ve read. Writing gives students a means to process new information and connect it with previous knowledge.

Exploring and experimenting: Inquiring children form questions, make predictions, test ideas, observe relationships, evaluate and make conclusions based on evidence. They create, invent and build things. They share ideas, make friends and express themselves. They seek truth and enjoy learning about the world around them. They set goals, stay motivated, reflect and develop higher order thinking abilities.

Reflecting & decision-making: It’s vital that students habitually evaluate their actions to determine which of behaviors lead to success and which lead to failure. In so doing they will understand themselves and how they learn. And they will be able to make adjustments for continual academic improvement.

Group Work

Benefits from small-group learning include:

- Celebration of diversity: Through small-group interactions, students find many opportunities to reflect upon, and reply to, the diverse responses that fellow learners bring to the questions raised. Small groups also allow students to add their perspectives to an issue based on their cultural differences. This exchange inevitably helps students to better understand other cultures and points of view.

- Acknowledgment of individual differences: When questions are raised, different students will have a variety of responses. Each of these can help the group create a product that reflects a wide range of perspectives and is thus more complete and comprehensive.

- Interpersonal development: Students learn to relate to their peers and other learners as they work together in group enterprises. This is especially helpful for students who have difficulty with social skills. They can benefit from structured interactions with others.

- Actively involving students in learning: Each member has opportunities to contribute in small groups. Students are apt to take more ownership of their material and to think critically about related issues when they work as a team.

- More opportunities for personal feedback: Because there are more exchanges among students in small groups, your students receive more personal feedback about their ideas and responses. This feedback is often not possible in large-group instruction, in which one or two students exchange ideas and the rest of the class listens.

Kinds of groups:

|

|

Personalities |

Learning styles |

Ability level |

Genders |

Relationships |

Cultures |

| Homogenous |

Similar |

Similar |

Similar |

Same |

Friends |

Only one |

| Heterogeneous |

Varied |

Varied |

Varied |

Mixed |

Not friends |

Multiple |

Kinds of group projects:

|

Cooperative Projects |

Collaborative Projects |

| In a cooperative project the teacher gives pupils the skills and instructions they need to be effective group members. Cooperative learning helps students become actively and constructively involved in their own learning, improve teamwork skills and resolve group conflicts. | In a collaborative project, the teacher gives minimal instructions so the group members must create and select strategies as a team. Collaborative learning results in deep understandings, high achievement, improved self-esteem, and better motivation to remain on task. |

Strategies for cooperative & collaborative learning:

- Give clear questions at the start, and show how they relate to students’ interests & abilities

- Resolve small-group conflicts as soon as they arise and show students how to prevent them

- Create a rubric to guide the learning process and to clarify the grading system

- Help students reflect on their progress on a regular basis

- Expect excellence from all students and let them know that you believe in them

Authentic Assessment

What is Authentic Assessment?

Authentic assessment is performance-based and requires students to exhibit the extent of their learning through a demonstration of mastery. Authentic assessment requires students to demonstrate that: 1) they know a body of knowledge, 2) they have developed a set of skills, 3) they can apply the skills in a ‘real life’ situation and 4) they can solve real life problems.

AIS has two templates for performance tasks:

- Performance Task Instructions TEMPLATE (based on the GRASPS approach)

- Performance Task Rubric TEMPLATE (prevents plagiarism and rewards enquiry/creativity/motivation/character)

Performance Task: ‘fact list’

- Performance tasks measure student progress in mastering ‘desired learning outcomes’

- Clear criteria (rubrics) are given to guide students and to judge their degree of proficiency

- Authentic scenarios are given to mirror problem solving that is required in the real world

- The tasks are worthwhile, engaging and relevant for students

- The tasks require the application of skills/knowledge learned prior to the assessment

- Students actively create products to demonstrate knowledge, skills or understanding

- Students do NOT passively select “a single correct answer”

Performance Task: ‘examples’

- Simulations

- Role-plays

- Portfolios

- Exhibitions

- Displays

- Performance of skills

Strategies for effective Performance Tasks

- Devise a task that immerses students in a ‘realistic’ project

- Give ‘real-world’ opportunities for students to apply knowledge

- Give ‘new situations’ for students to apply their learning

- Give ‘challenging’ tasks that are ‘achievable’

- Provide choices in tasks; let students choose how to show mastery/competence

- Provide time for students to think about and do assignments

- Enable students to take on a variety of roles

- Encourage collaboration and discussion of new ideas

- Encourage divergent thinking

- Encourage students to link new information to personal experience, prior knowledge

- Integrate tasks with desired learning outcomes, curriculum content and workplace skills

- Ensure that students have opportunities to develop critical thinking and problem solving

- Provide clear evidence that students have achieved the desired learning outcomes

- Create a timeline to separate tasks into sequential, manageable chunks

- Give plenty of time (1-4 weeks)

Assessment of Performance Tasks

- Assess for learning purposes; not just for grading purposes

- Provide ongoing feedback throughout the project that students can act upon

- Assess the ‘process’ as well as (or instead of) the ‘products’

- Assess the students’ social, cognitive, and reflective processes of learning

- Use criteria that have been developed (or negotiated) with students

- Incorporate self, peer, client and teacher assessment

- Ensure there are multiple links and solutions, not just one right answer

- Encourage multiple modes of expression

- Emphasize critical thinking skills: analyze, compare, predict, hypothesize, etc.

Self-learning through Performance Tasks

- Let students help define the project goals (personal and class)

- Require students to set personal goals, revise, rethink and modify their strategies

- Have students self-evaluate; think about how they learn well/poorly

- Encourage students to see the connection between effort and results

- Involve students in the development of standards and assessment criteria

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment is the use of non-graded tasks and activities to guide teaching and learning. It contrasts with summative assessment, which occurs at the end of a learning unit to rate each student according to the amount of learning that has taken place.

How is formative assessment useful?

Formative assessment reveals the thinking and understanding of each student, which, in turn, reveals how the teaching should be adjusted. For example, the teacher might decide to re-teach a concept, use an alternative instructional approach, increase or decrease content, or offer a student more opportunities for practice and reinforcement.

How frequently should formative assessment happen?

Teachers should assess their students frequently and in multiple ways to build up an accurate picture of what students know and understand. They should aim to gather a “photo album” rather than a “snapshot” of their students. In this way, the teacher can identify trends, and determine how the student is evolving as a learner.

What are the five steps in AIS’ formative feedback system?

Step 1 – Establish purpose

The teacher clearly communicates the learning objectives and required standards to the students at the start of every lesson. These should be listed in written form as “I can…” statements. This practice helps students to stay on topic and see the relevance of the feedback they receive. Our teachers reach agreements with colleagues on what constitutes ‘high quality work’. And, they look for opportunities to develop individualized learning aims with students so each learner plays an active (not passive) role in his or her learning.

Step 2 – Be a model

Our teachers think of their students as young apprentices who want to emulate the ways that the teacher thinks and solves problems. To be a model, our teachers use the ‘think-aloud’ method, wherein they verbalize their thoughts, feelings and actions in order to demonstrate proficiency. This enables the pupils to see how an ‘expert’ thinks while solving tasks and problems.

Step 3 – Guide instruction

As students begin to get their feet wet with new skills, ideas and contentthe teacher uses questions, prompts and cues to systematically direct each learner towards success. The questions should deepen the student’s thinking and/or check for understanding, the prompts should cause the student to do something cognitively, and the cues should nudge a struggler towards helpful resources or actions. It is essential to gradually reduce the amount of guidance over time so that each student receives sufficient help to move forward without developing ‘learned helplessness’, wherein they become dependent on the teacher for answers.

Step 4 – Give group work

At AIS we give a wide variety of group activities because differentiated, activity-based classrooms are much better for developing understanding than teacher-centered classrooms for the following reasons: 1) student products provide good fodder for discussing (and/or gauging) student understanding, 2) student activity provides good information to decide the best next steps, 3) teachers that spend a lot of time talking have little time left over for gauging understanding, guiding instruction, or trying new approaches, 4) peer interactions deepen understanding, develop academic language, trigger higher-level thinking and increase student motivation, and 5) teachers feel more successful and less stressed in student-centered classrooms, which gives them more positive energy to share with their pupils.

Step 5 – Give independent Tasks

Independent tasks are given once the students have had the opportunity to build significant understanding. AIS teachers design independent tasks that trigger creativity, as the ‘creative process’ isn’t something that happens after the ‘learning process; it is the learning process! Additionally, our teachers constantly analyze the effectiveness of their activities: if the activities don’t reveal or deepen understanding then they should be replaced by new activities. Finally, our teachers ensure that each child is challenged but not frustrated, which means that the individual tasks must be differentiated. Some of the ways to differentiate individual work include: 1) requiring some students to answer fewer questions than others; 2) requiring some students to answer more challenging questions than others; 3) requiring some students to use different resources or texts than others; and 4) requiring some students to create different products than others. Is this fair? Yes! At AIS, “Fair isn’t equal. Fair is giving each child what he or she needs to reach his or her full potential.”

Guided Instruction

What is Guided Instruction? Guided instruction happens while students are in the stage of doing. It requires the teacher to be dynamic, constantly adjusting to the learners’ needs and making the appropriate instructional moves to drive their learning forward. During guided instruction the teacher must decide when to: 1) check for understanding, 2) scaffold with prompts or cues to strengthen a learner’s understanding, and 3) provide direct instruction and modeling. The teacher’s aim should be to gradually release responsibility to the students, which means that over time the students become better at learning and applying understanding on their own. The art of guided instruction then, is to give sufficient assistance to pull learners forward without stifling their independence.

Scaffolding:

Teachers can scaffold to:

|

|

Types of questions used for guided instruction:

A question falls into one of two categories: 1) productive and 2) reproductive. Productive questions cause students to synthesize ideas, evaluate information and create new ideas. Reproductive questions require students to recognize and recall facts. Both types of questions can be helpful but productive questions trigger much richer discussion for deepening student understanding and showing the teacher what needs to be done next.

Elicitation questions draw on previously taught information. The depth and accuracy of responses reveal what students know.

Example: “What do you know about 1st century Rome?”

Elaboration questions require students to expand on an initial response. They aim to reveal the limits of a student’s understanding.

Example: “Can you tell me more about the Roman judicial system?”

Clarification questions require students to provide additional information to clear up any ambiguity in their initial responses.

Example: You used the term ‘vindictive’. What do you mean by that?”

Divergent questions require students to draw information from multiple sources to develop understanding.

Example: The Romans formed the Roman Catholic Church. So why did they crucify Jesus?

Heuristic questions require students to use intuitive problem-solving skills.

Example: “There are a lot of Roman soldiers in this painting. How might you estimate the total number?”

Reflective questions invite speculation and opinions.

Example: “On the whole, did ancient Roman civilization advance or hinder human progress”

Types of prompts used for guided instruction

Experts are adept at knowing what is important and what is not. Novices, however, have difficulty knowing what information is important so prompts are needed to help them identify which information and behaviors are useful for solving a problem.

Background knowledge prompts help student to recall what they already know in order to solve a problem or answer a question.

Example: “True, but I’m thinking about another mechanism. Think about yesterdays lesson on enzymes.”

Procedural prompts are used to guide students through the steps of a complex task.

Example: “Set your microscope to 10X before inserting the slide. Use the course focus knob to locate your specimen…”

Reflective prompts are used to get students reflecting on their learning.

Example: “What do you know about World War II that you didn’t know before?”

Types of cues used for guided instruction

Cues take back some responsibility (but not all) from the learner. They shift the learner’s attention to important information. Cues do not give the answer but they provide a path to follow in order to reach the answer.

Visual cues use color, light or graphics to highlight important items.

Example: Bold font, underlined words and highlighted text.

Verbal cues draw the student’s attention to important information with the use of tone, intonation, expression, etc.

Example: “Are you sure Jenifer is the antagonist?” (Said with a strong questioning tone)

Gestural cues include facial expressions and movements that enhance spoken language.

Example: “There was no way the Chinese Emperor could accept his terms!” (Said with forward and back finger pointing)

Grading

Rubrics

- AIS teachers provide rubrics for all graded tasks

- Students know (and understand) the rubric ahead of time (i.e., before starting any work)

- Each criterion in the rubric matches learning outcomes in the curriculum

- There is often a ‘low-weight’ criterion for neatness/grammar/punctuality/organization

- There is often a criterion to reward creativity, innovation & risk-taking

Portfolios

- Students maintain a portfolio containing ALL of their assessed work (both formative and summative)

- Student portfolios are tidy, sequential and kept in the classroom where they are used for cognitive coaching

- Each assessment has a completed cover sheet (with student reflection) & a rubric completed by the teacher

Self-grading

- Self-grading is a good strategy to help students reflect on their work and to see the connection between their output and their grades.

- If students self-grade the teacher must also grade with the same rubric. The teacher’s grades (not the student’s) go in the grade book.

Grades

- Students are not graded on any work until they have been given sufficient practice-work & feedback

- Grade weights are lower near the start of a unit/quarter and higher near the end

- Partial credit is awarded on progressive questions (early wrong answers are carried forward in the marking)

Fairness

- All major assessments are calendared weeks in advance

- Tasks are neither too easy nor too challenging (this may require differentiation)

- Teacher avoids tricky language or cultural bias that might put ESL students at a disadvantage

- Students are sometimes able to negotiate their preferred mode of assessment: oral/written/application/etc

Performance tasks

- Teacher chooses activities that are engaging and challenging for all students (teacher differentiates)

- Teacher assesses in a variety of ways: individual-work/group-work/research/enquiry

- Teacher uses open-ended questioning and student/teacher interviews to gauge student understanding

- Skills are assessed in natural situations (e.g. students are assessed using – not drawing – microscopes)

Homework

- Teacher always uses the homework journal (before and after the assignment)

- Teacher uses feedback from the homework journal to improve future assessments

- Homework may be graded as ‘complete’, ‘tidy’, ‘creative’ etc. but correctness should not affect the students official grades.

- Students are given prompt feedback and the teacher ensures that they apply it in meaningful ways

Long-term Projects

- Teacher sets ‘real-world’ tasks that are relevant to students

- Students have considerable scope to choose topics and gain a sense of ownership for the work

- Activities are time-efficient: the amount of learning justifies the total time invested by the students

- There are two deadlines; one for feedback and one for final grading

Group-work

- Beginner-level kids don’t gain advantage from the advanced-level kids, and vice versa

- Grades are based more on Learning Behaviors than on the final product

- Students are interviewed individually by the teacher to verify individual learning

Quizzes

- Quizzes are announced well in advance, and the timings are adjusted to match student readiness

- Knowledge is assessed with sufficient coverage to minimize students getting ‘lucky’ or ‘unlucky’

- Open-book quizzes are used to assess higher-level thinking but not lower-level thinking

Tests

- Each test is preceded by a ‘non-graded pre-test’ that is marked & returned 1-week prior to the actual test

- Before a ‘pre-test’, students are given a detailed ‘green/yellow/red’ study-guide that matches the curriculum

- Questions on: ‘low-level-thinking’ (no options); ‘mid-level’ (no options); ‘high-level’ (multiple options)

- Tests contain new & challenging questions: low emphasis on memorization, high emphasis on understanding

- Questions have wide coverage of unit but don’t go beyond the curriculum objectives

- Meanings of operational terms like discuss/argue/contrast/justify/evaluate/explain are known by all students

- We don’t let students submit blank answers on tests